Nabbing Criminals by Using Brainwave Analysis

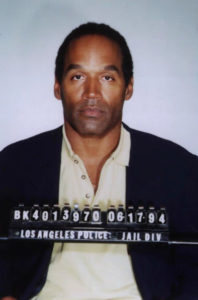

In a dramatic courtroom demonstration, O. J. Simpson struggled to put on a pair of blood-soaked leather gloves recovered from the murder scene—damning physical evidence of guilt if indeed the gloves were his. “If it doesn’t fit, you must acquit,” defense attorney Johnnie Cochran proclaimed to the jury. Whether Simpson’s failed efforts were theatrics or honest is difficult to judge, but Simpson was unable to slip his hands into the gloves easily and he was acquitted. Questions lingered over whether the blood saturated gloves had stiffened and shrunk, and the fit was further impeded by the rubber gloves Simpson was required to wear underneath the evidence gloves.

Had the jury been provided with Simpson’s brainwaves evoked in reaction to seeing the gloves, there would have been no need for the test fit. In fact, there would have been no need at all to question Simpson about the gloves. A tell-tale response in his brainwaves would have disclosed whether or not he recognized them.

The ability to tap into the brain’s electrical activity through sensors on the scalp (EEG) can accurately reveal if a person is concealing information. In contrast, a lie detector machine (polygraph) measures the body’s stress response that frequently accompanies deception, but this is an indirect and imperfect way to determine whether a person is telling the truth. As explained in my new book, Electric Brain (BenBella, February 2020), the brain’s operation in processing information and in thinking is becoming better understood, and technical advances in monitoring and interpreting the brain’s electrical activity through the scalp can reveal a person’s thoughts and emotions. This capability promises to make deception impossible.

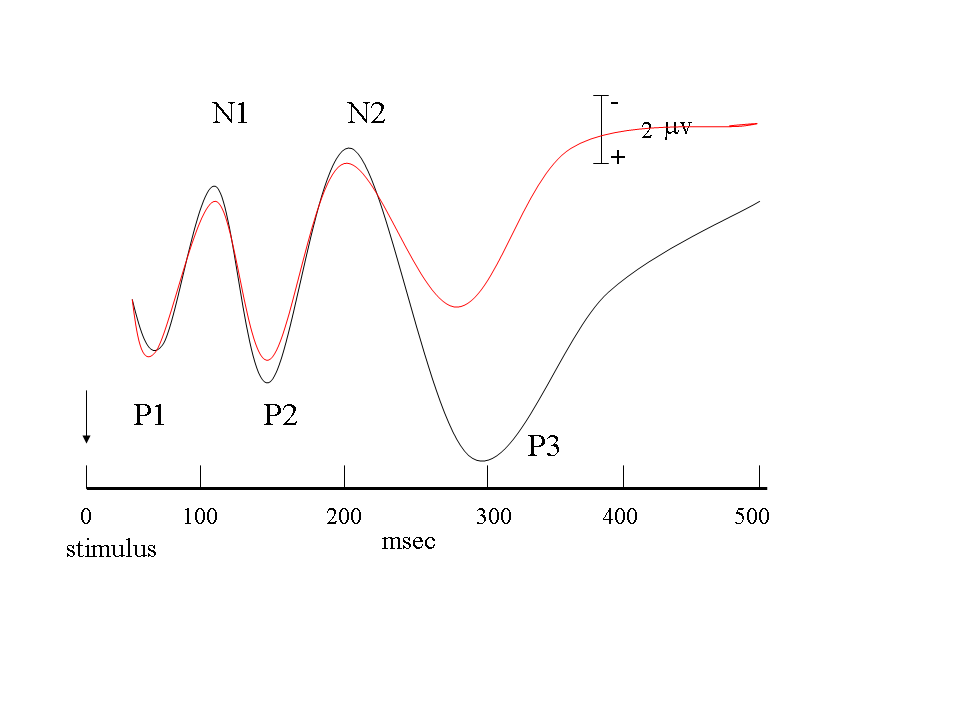

The ability to tap into the brain’s electrical activity through sensors on the scalp (EEG) can accurately reveal if a person is concealing information. In contrast, a lie detector machine (polygraph) measures the body’s stress response that frequently accompanies deception, but this is an indirect and imperfect way to determine whether a person is telling the truth. As explained in my new book, Electric Brain (BenBella, February 2020), the brain’s operation in processing information and in thinking is becoming better understood, and technical advances in monitoring and interpreting the brain’s electrical activity through the scalp can reveal a person’s thoughts and emotions. This capability promises to make deception impossible.Brainwaves arise from the combined action of thousands of neurons in the cerebral cortex firing electrical impulses as they process mental information. When the brain’s electrical activity is measured by EEG immediately after a stimulus is presented, a ripple in the ongoing brainwaves is produced, called an event-related potential (ERP). The immediate ERP brainwave reflects neural circuit activity engaged in receiving the sensory information; that is, the mechanics of sensory perception. But this is followed quickly by the brain’s cognitive analysis of the event; for example, judging whether the event is important or novel.

If the stimulus has special significance in a given situation, a characteristic peak in the brainwave will erupt one-third of a second after the stimulus is presented. This lightning-quick electrical event is called the “Aha!” response, and it is evoked when something grabs our attention. The tell-tale response is named the P300 wave because it peaks about 300 milliseconds after the stimulus is presented and it has a positive voltage polarity. For example, as you read the sentence that “I take my coffee with cream and dog,” a P300 wave just erupted in your brain. Had the sentence read “cream and sugar,” that would not have happened. Likewise, if the gloves were shown to Simpson and they had no significance to him, there would be no “Aha!” brainwave evoked. If, however, they were indeed the gloves he wore the night he allegedly murdered his wife and Ron Goldman, that recognition would have caused a P300 tsunami. “If there is a brainwave kick, you must convict.”

“Aha!” P300 brainwave response

Even in cases where no deception is involved, this brainwave analysis could be extremely valuable in law enforcement. Witnesses and victims in crimes are often unable to recall events accurately and in detail. When presented with sketchy evidence, false memories and misidentifications can derail the accuracy of testimony and result in erroneous convictions. Brainwaves, though, reflect the high-speed, nuts-and-bolts preconscious information processing in our brain. If any traces of experience from an event remain in the brain—even unconsciously—this EEG analysis can reveal it.

The method has not yet found wide-spread acceptance in interrogations and courts of law, but it has been used. On August 5, 1999, neuroscientist Lawrence Farwell administered such an EEG test to murder suspect J. B. Grinder, to determine if specific details of the rape and murder of Julie Helton were recorded in the suspect’s brain. The results revealed that information only the murder would have known was present in the suspect’s brain. Grinder pleaded guilty and later confessed to murdering three other women.

EEG technology and the ability to analyze complicated brainwave signals have advanced tremendously since the 1990s. In addition, other powerful methods of monitoring the brain’s electrical activity through the scalp, such as functional magnetic brain imaging (fMRI), and infrared lasers that penetrate the scalp (near infra-red spectroscopy), can detect and analyze neural activity in brain circuits throughout the brain, not just in the cerebral cortex as EEG measures. Using these methods together with advanced machine learning to analyze the brain responses, neuroscientists can read a person’s thoughts and emotions and see how specific neural circuits in an individual’s brain respond to stimuli. As this technology and a deeper understanding of how the brain functions at a neural circuit level continue its rapid advance, the ability to directly interrogate a person’s brain will become more powerful and more accurate. It is only a matter of time before this technology is adopted by interrogators and courts of law.

Before that can happen, the methods must be proven reliable in practical application, not just in laboratory settings, and this high bar is what is limiting its use now. Also, recognition does not mean culpability. A person may have visited the Walmart store where a robbery had been committed, and their P300 brainwave would peak in response to viewing the crime scene photo, but that does not mean that the individual had any involvement in the crime. An additional complication is that individual differences in the P300 response are found that are related to level of arousal, working memory, cognitive capacity, personality (notably impulsivity and novelty seeking), age, neurological and psychological factors.

Brainwave analysis may not be quite ready for use in solving crime and rendering justice in court, but there is little doubt that it will be soon. At that point, present methods, such as waterboarding to extract information, polygraph tests of anxiety while being questioned, and trial-by-fire tests of whether or not a glove fits in a courtroom spectacle, will seem primitive.

First published in Psychology Today