Big Mystery About the Little Brain

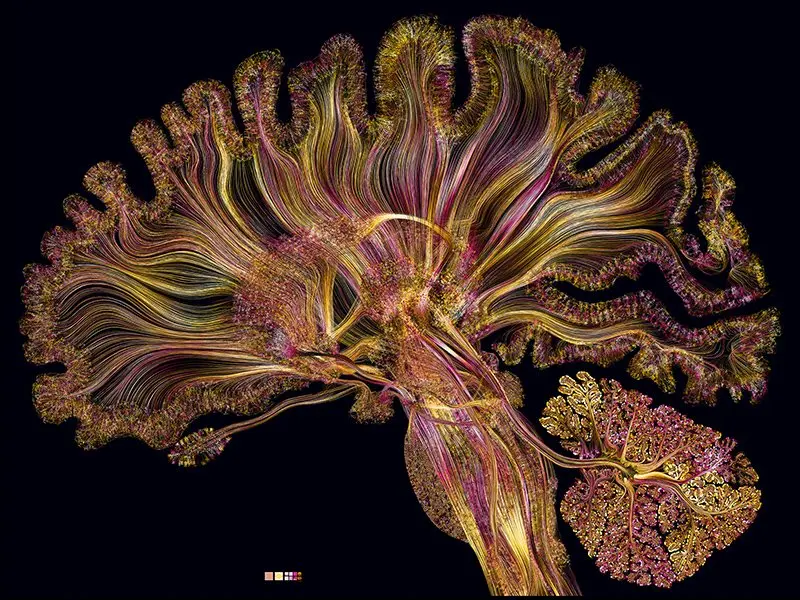

Cerebellum from neuro artist Greg Dunn. Copyrighted and used with permission. See:

https://www.gregadunn.com/

With all the stunning advances in neuroscience it may come as a surprise that a major part of the brain is a mystery to scientists. It is not a small oversight. This peculiar brain lobe contains ¾ of all the brain’s neurons! Astonishingly, its cellular structure is unlike anywhere else in the brain. The neurons here are organized with printed circuit board-like wiring in an almost crystalline arrangement, in contrast to the tangled thicket of brain cells elsewhere. The mystery extends back to the 1700’s when scientists first proposed that electricity powers the nervous system. The quandary persists to this day, as I found while attending the Society for Neuroscience Annual meeting in Washington, DC in November 2023, which is the largest meeting of neuroscientists in the world.

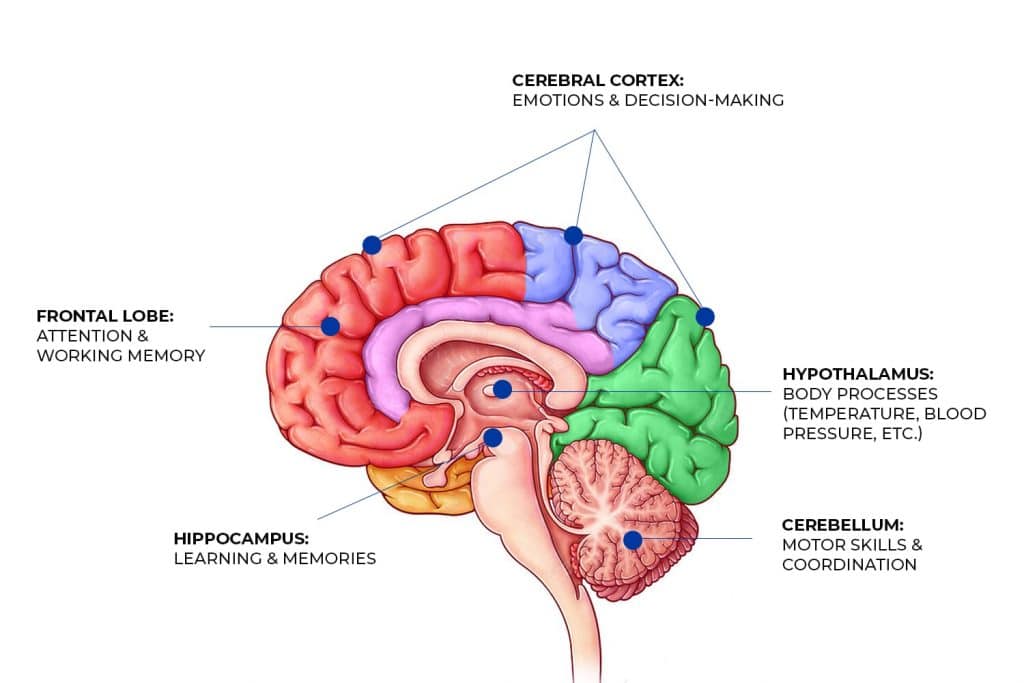

I am referring to the cerebellum, Latin for ‘little brain,’ situated like a hair bun at the back of the brain. You may have learned that the function of the cerebellum is to control body movement, but scientists now suspect that long-standing view is myopic.

Encyclopedia articles and textbooks underscore the fact that the cerebellum’s function is to control body movement. There is no question that the cerebellum has this function, but new research is revealing that it does much more.

Before I share these transformational findings with you, a bit of history will help us understand how the cerebellum’s function in controlling movement originated and what changed the long-held view.

Twists and Turns in the Story the “Little Brain”

In the 1780’s, Luigi Galvani, at the University of Bologna, noticed that frogs’ legs hanging from brass hooks on his metal banister twitched whenever a breeze knocked them against the iron. Animal electricity, he surmised, must flow through the nervous system to power muscles. His contemporary, Alessandro Volta, at the University of Pavia, took up the research. In 1799 he invented the battery, built from moist paper discs sandwiched between silver and zinc plates stacked like Oreos in a brine. He found that a jolt from his battery set frog legs hopping.

That discovery sparked a new idea in the mind of Luigi Rolando, at the University of Sassari, about what the cerebellum did. In many ways, he thought, the cerebellum resembles Volta’s battery. The cerebellum is compressed tightly into layers, like a Japanese fan, but wadded into a tight ball as if to toss it into a wastebasket. If the folds were spread out flat, the surface of the cerebellum would span over three feet! The organ that produces electricity in electric eels is also made up of stacks of tissue. The cerebellum, Rolando surmised, must be the brain’s battery! To prove it, he removed the presumed biological battery from a sheep’s brain and found that the animal could not stand up.

The brain battery hypothesis of the cerebellum soon faded, but obvious difficulties with balance and movement in patients suffering trauma to the cerebellum left no doubt that it was critical for coordinating movement.

A turning point came in 1998 when neurologists Jeremy Schahmann and Janet Sherman of Massachusetts General Hospital examined patients with damage to the cerebellum and reported wide-ranging disabilities in cognitive and emotional functions. These high-level non-motor functions challenged conventional thinking and left neuroscientists baffled. “Precisely what that cerebellar role is, and how the cerebellum accomplishes it, is yet to be established,” they concluded.

“I definitely believe that persists today,” Diasynou Fioravante says when we meet together with Stephanie Rudolph at the Society for Neuroscience Meeting, where the two neuroscientists organized a symposium on newly discovered functions of the cerebellum unrelated to motor control. But, she and Rudolph eagerly add, now scientists are forming a much better picture of what the cerebellum does from new experimental techniques.

With this background, now read the full article on Quanta Magazine