The Neuroscience of Violence

We are on the brink of a new understanding of the neuroscience of violence. Like detectives slipping a fiber optic camera under a door, neuroscientists insert a fiber optic microcamera into the brain of an experimental animal and watch the neural circuits of rage respond during violent behavior.

Neurons genetically modified to flash bursts of light when they fire reveal where these circuits of rage are in the brain, and neuroscientists can stimulate or squelch the firing of a neuron they target by laser beam. With the flip of a switch neuroscientists can launch an animal into a violent attack or arrest a violent battle underway by activating or quelling the firing of specific neurons in the brain’s rage circuits. Technological advances in monitoring brainwaves and brain imaging are bringing new insight into this same circuitry at work in the human brain. These circuits of aggression are part of the brain’s threat detection mechanism embedded deep in the unconscious region of the brain where sex, thirst, and feeding are also controlled.

Violence, like all human behavior, is controlled by the brain. From the everyday road rage, to domestic violence, to a suicide bombing, the biology of anger and aggression is the root cause of most violent behavior. Violence can activate some of the same circuits of addiction in individuals, especially males, who seek out violence. A new study published in the March 7, 2016 issue of Nature Neuroscience, by Annegret Falkner and colleagues, identifies specific neurons in the hypothalamic attack region that are activated when male mice seek out violent aggressive encounters with other male mice.

The social implications of this new line of research are profound. Struggling to comprehend a suicide bomber’s “thinking” or police searching for “motives” in cases where violence is driven by perceptions of threat, alienation or emotion is a search in vain. Such violence is not driven by reason. It is driven by rage. Violence at political rallies, terrorism, and horrifying workplace shootings bewilder us, but neuroscience research offers a new perspective on violence.

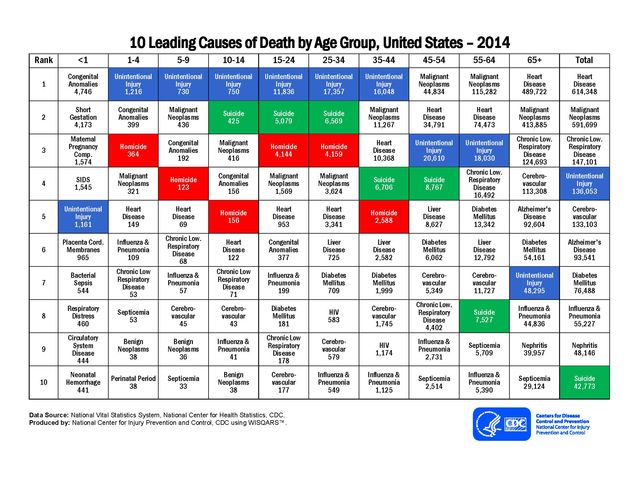

Viewing violence narrowly from the perspective of psychological dysfunction shirks the larger truth that the biological roots of rage exist in all of us. The leading risk of death throughout the prime of life is not disease. It is violence. If you survive into old age you will most likely die from disease, but according to CDC statistics for deaths in the United States for the year 2014, life ends at the hand of another human so frequently, that from early childhood through middle-age, homicide is the third to 5th most common cause of death in all age brackets between 1-44 years.

A psychopath or a foreign terrorist is not the likely villain. The data show that the murderer is twice as likely to be your friend or acquaintance as it is to be a stranger. Deadly violence against oneself (suicide) is second only to accidental injury as the most frequent way we die between the ages of 10 and 34.

The most important factor in violence is not pathology, psychology, or politics– it is biology. Nine out of ten people in prison for violent crime are men. Males die from homicide at three times the rate of women. When the victim is a spouse or intimate partner women are murdered at 3.3 times the rate of men. Males commit suicide at four times the rate of females. Violence and maleness is a biological fact that runs through the vast diversity of cultures and through our ancestral tree to other primates.

We have neural circuits of rage and violence because we need them. As a species we needed deadly violence to obtain food, to protect ourselves, our family, our group, and unfortunately we still need them today. Order in society is maintained through violence, meted out methodically by police and nations according to laws that benefit society at large, but this organized violence is founded on the same neurocircuitry of aggression wired into the human brain of every individual.

Most of the time the neural circuits of aggression are life-saving, as when a mother instantly reacts aggressively to protect her child in danger, but sometimes they misfire and violence explodes inappropriately, as in a road rage shooting. The pressures of modern life constantly press on these triggers of rage. International communication and high-speed transportation increase opportunities for conflict between different groups of people. Weapons of violence amplify the lethal effects of one enraged mind well beyond the power of any individual to combat with bare hands. Add to this the toxic effects of psychoactive drugs for treating mental illnesses and drugs of abuse, compounded by the increasing stress, crowding, and sensory bombardment of the modern world, and we see the human brain struggling to cope with an environment it was never designed to confront.

The CDC statistics strongly suggest that in addition to understanding the biological basis of disease, there is a much greater unmet need for neuroscience research to understand the biological underpinnings of violent behavior.

Reference

Why We Snap: Understanding the Rage Circuit in Your Brain, by R. Douglas Fields, Dutton, January 2016.

Kavli Conversations on Science Communication, The Fragile Brain: Neuroscience Hits Home, April 20, 2016.

Article modified from: R. Douglas Fields The Science of Violence, Psychology Today, April 27, 2016.

First published on: R. Douglas Fields, BrainFacts.org, April 29, 2016.

I enjoyed “The Other Brain” and have slowly got through half of “Snap” as it keeps triggering ideas in my mind as to how some problems need more expert input than we are giving them. At the moment in Australia, there is an enormous amount of focus on violence in the family, or home. Sadly I suspect the emphasis is on instituting simplistic and expensive programs to show governments and people are doing something about the apparent problem. My suspicion is that most of the money will be wasted and come to nought. Too many non-experts are proposing solutions and yet they seem to demonstrate no, or very little, understanding of the unconscious or intuitive mind and how little the conscious mind contributes to this problem. Your book is not available generally here until August so I got my copy from the UK. We might need some of your expert sources to give advice to where we need to go.