Electric Brain Wins Two Book Awards

I am honored that my new book Electric Brain has received two awards. It just received the Gold award for 2021 in the category of Science Books from the Independent Publisher Awards (IPPY Awards). “The IPPY Awards reward those who exhibit the courage, innovation, and creativity to bring about change in the world of publishing.”

I am honored that my new book Electric Brain has received two awards. It just received the Gold award for 2021 in the category of Science Books from the Independent Publisher Awards (IPPY Awards). “The IPPY Awards reward those who exhibit the courage, innovation, and creativity to bring about change in the world of publishing.”

This comes on the heels of receiving the 2020 Book-of-the-Year Silver Award from Foreword Indies Reviews. “Foreword Reviews is dedicated to the “art” of book reviewing. . . Our book-industry journal is designed for a discerning readership—in recognition of the fact that quality paper, generous use of white space, and creative design encourages a time investment by readers.”

It is wonderful to receive appreciation of my book from other bibliophiles, and these awards provide a valuable service to readers searching for worthy reads amid the blizzard of titles. This recognition also gives me occasion to share some of the backstory to Electric Brain—what sparked the idea and some insight into my approach in writing it.

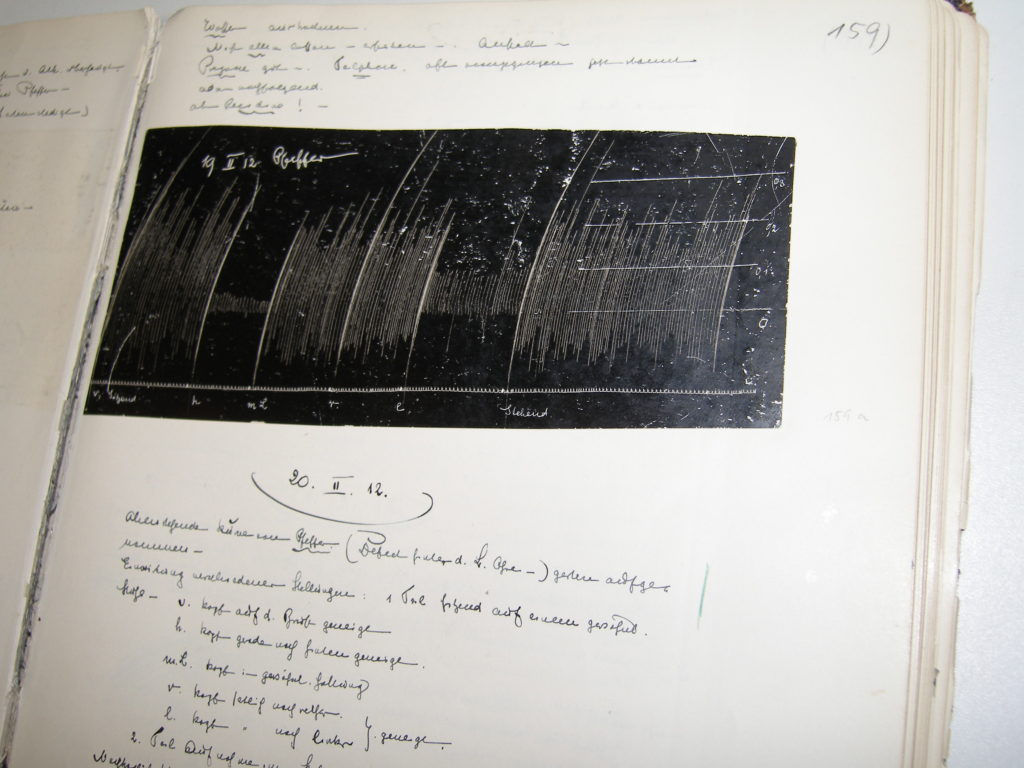

I became fascinated with the subject of brainwaves while visiting Jena, Germany, doing research for my earlier book, The Other Brain (2009, Simon and Schuster). That book is about glia, which are brain cells that communicate without using electricity. At the time, the idea that glia could control electrical activity in the brain was very controversial. One of the most compelling observations was that glial cells, called astrocytes, had a powerful influence on brain seizures. Recordings of brainwaves are the primary way that seizures are studied, so my research to track down primary sources of information led me to Jena, Germany, where the first brainwaves in humans had been detected by a reclusive doctor, Hans Berger, doing experiments in secret on mental patients and on members of his own family. Primary sources are essential, because so often information gets distorted from retelling or it may not be well sourced or accurate. That proved to be the case for brainwaves. I soon discovered that the accepted history was not accurate; indeed, the biographies of Hans Berger at the time were a whitewash.

My intrigue grew as I traveled around the world to examine the original lab notebooks and experimental apparatus of pioneers in brainwave research, and to visit contemporary neuroscientists who were working at the forefront of brainwave research. The convoluted story of how brainwaves were discovered was shrouded in mystery, and I came to understand that this information fog arose from a turbulent mix of science and society: Nazis, war, and a consequence of how science works and sometimes fails. In an era of gas lamps, when electricity was as mysterious as dark matter today, lone scientists were working decades ahead of their time, trying to comprehend the startling electrical waves they found emanating from the brains of animals and people, while other scientists dismissed brainwaves as nothing but experimental noise, or a useless byproduct of the brain at work.

I became captivated while holding Hans Berger’s century-old laboratory notebooks in my hands—the same books that Berger had held as he penciled down the results of the first experiments on brainwaves in humans in the early 1920’s. Who was this enigmatic man? What did he think he had discovered? What were the reactions of other scientists at the time to this reclusive doctor claiming that electromagnetic waves radiated out of his psychiatric patients’ brains?

Clearly the story of brainwaves was larger than could be encompassed in my book about glia. As the German countryside streamed past on the train back to the Berlin airport, the idea of writing a new book devoted to brainwaves arose.

Book publishers I approached at the time were not interested—too esoteric and complicated. It was disappointing, but I could see their predicament. There were no popular books on the subject, so editors and publishers could not conceive how my proposal of what seemed to most people to be a medical book, would be of general interest.

But what I had in mind was not a medical book–and times change. Brainwaves began to impact my own laboratory research. Over the ensuing years I witnessed an explosion of interest in brainwaves among neuroscientists that spanned all fields from physiology to psychology. As a neuroscientist, the magnitude of this discovery was obvious to me. Our old notions of how the brain works were inadequate, and I could see how cognition and the operation of neural networks in the brain are orchestrated by these waves. (My experiments focused on brainwaves in the cellular mechanism of memory.) So I began writing snippets of the book. Some bits I published in magazine articles, blogs, and science news reports, but most of the text was just the bones of what I hoped would one day flesh out into a book for the general reader.

The book is structured in three parts, each one with a different scope and different treatment. Part I reveals the fascinating and little-known story of the discovery of brainwaves, based in part on new information from my search for primary sources.

Part II explains the science—what brainwaves are, how they are studied and manipulated, and it confronts the current controversy that brainwaves are generating in the field of neuroscience. The approach in Part II is largely first-person narrative reporting. There is no doubt in my mind about the fundamental importance of brainwaves in brain function and dysfunction, but I did not want to write a book that argued my viewpoint. I wanted to capture this scientific transformation for the general reader as it is unfolding now, to give insight into how science works; to bring readers into the laboratories of my colleagues around the world and to let them see the data, hear the scientists’ beliefs and uncertainties, and to form their own conclusions.

Part III surveys the applications of brainwaves in diagnosis and treatment. Despite the controversy over brainwaves among neuroscientists, no one doubts the importance of analyzing brainwaves or of manipulating electrical activity in the brain for diagnosis and treatment of a wide range of neurological and psychological disorders. Most people have no idea how important brainwaves are for diagnosing brain and mental disorders of all kinds, and how this capability will transform medicine and change society in profound ways.

This section calls on expository writing primarily, but for storytelling purposes and to sustain interest, first-person reporting is interjected to liven up this section. That is also true for Part I, to tell the history in a compelling way. Some of the most memorable experiences for me in my eye-witness reporting in this third section were hearing from people paralyzed by spinal cord injury who have electrodes implanted in their brains to operate prosthetic devices, and being able to go inside the operating room to see surgeons implant a completely new experimental device threaded into the brain through blood vessels to monitor and manipulate the brain’s electrical activity.

I had intended to write a svelte volume, but Electric Brain expanded into 470 pages including references to the scientific literature, because of the challenge of wrangling all the information in Part III. Documenting the practical applications of brainwave analysis, neurofeedback, and brain stimulation in neurological and psychiatric disorders greatly expanded the book. The explosive pace of new research made it a challenge to keep up, and I felt swamped by the rapidly expanding impact of brainwave research on diverse areas of brain science and medicine. If I covered brainwaves in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disorder, and traumatic brain injury, how could I leave out ADAH, PTSD, chronic depression, and other concerns some readers would have?

But there is an underlying theme that runs throughout the book, because it is this theme that propelled all research on electrical energy in the brain throughout history—the mystery of how it is that this couple of pounds of convoluted flesh can think, and make us human.

The book is also forward looking. Things will never be the same now that the capability to read minds, control brain and behavior, and meld minds and machine are realities. For the first time in human history, our species has developed the capability to interrogate and manipulate brain function directly by using electricity, to control behavior and disease, and to know the capabilities your individual mind. Monitoring electrical activity in your brain can reveal not only how your brain may be failing, but also what your own brain can and cannot do well– what subjects you will excel in or struggle with in school, or what professions are best suited to you.

I couldn’t let the idea go. Even as I wrote another book on the neuroscience of sudden aggression, Why We Snap (Dutton/Penguin, 2015), I kept collecting information, conducting interviews, and learning about brainwaves. Then suddenly brainwaves and brain-computer interfaces broke out in the news. The discoveries had escaped laboratories and were being snatched up by entrepreneurs to make devices to read minds, transmit thoughts, and control machines by linking mind and computer. The time had come, it seemed.

After a decade of mulling over the idea sparked while visiting Hans Berger’s laboratory in Jena, I pitched my book proposal for a second time. With the help of my outstanding Literary Agent, Andrew Stuart, who offered it to BenBella Books, I found interest now. He put me in touch with Glenn Yeffeth, Publisher of BenBella Books, who was intrigued. “Is this real or something you foresee developing in the near future?” he asked cautiously after I told him about mind reading, melding minds and computers, controlling brains by electrical stimulation and being able to know an individual’s cognitive strengths and weaknesses by tapping into the brain’s electrical activity. I understood his skepticism because there is so much hype, superficiality, and misinformation about brainwaves in popular magazine articles and in science fiction. “I am a neuroscientist,” I replied. “All that any scientist has is their credibility. This is real and it is happening now.”

The idea sparked in Jena, became a reality.